When I graduated from high school, I had two careers in mind: famous novelist and famous actor. I had no idea what went into either, but I figured I could probably manage both, if I did it right. Look at Tom Hanks, he's a famous actor and a novelist who also happens to be famous. Except I wanted to be a gestalt of Stephen King and Jack Nicholson.

I figured I had the famous novelist part taken care of, because I was going to be a Creative Writing major at the University of Arizona, but I wasn't sure how to go about the famous actor part. Being a theater minor didn't put you in the middle of the action, the main stage was reserved for theater majors, or people who really knocked their socks off. So, not knowing any better, I auditioned for the main stage theater.

In the words of "Easy Rider," I blew it.

Halfway through, I blanked on the piece I'd memorized, because I'm a dummy and picked something new to memorize in two days instead of the tried and true trick of performing something you had previously memorized and performed. I probably only blanked for a couple of seconds, but it felt like twenty minutes, and I was lucky to finish the damn thing before I croaked "thank you!" and retreated offstage.

Luckily for me, I had a backup.

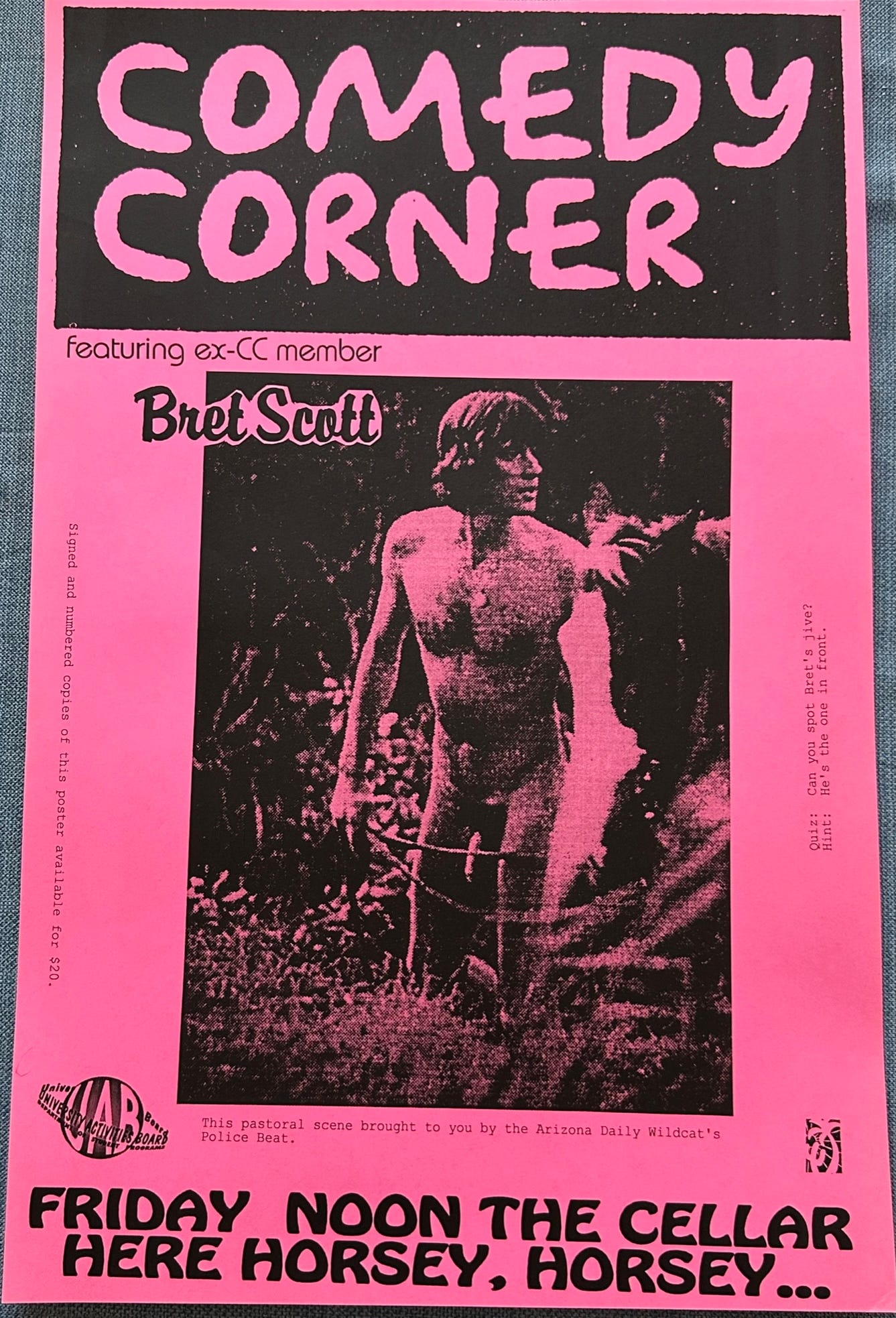

A friend of mine from high school had told me about the U of A group, Comedy Corner, a weekly sketch comedy show in the vein of “Saturday Night Live,” that had been around, to that point, around twenty years or so. They wrote and performed a new hour of original comedy every week, and every year they held auditions for performers and writers to replace the graduates who'd left the group. I wanted to audition as a performer, but having learned my lesson about having a backup plan, I hastily wrote a pair of sketches, one that sucked, and one that I thought was halfway serviceable.

I showed up to the performance space, a large room on the basement level called The Cellar, constructed in the spitting image of a brick wall comedy club, with a tiny stage up front, and rows of tables in the darkened audience. The veteran members of the group sat behind tables they'd put together, and spent the afternoon alternately ripping us new assholes with their hilarious insults, and trying to make each other laugh. It was much harsher than the theater audition. That actually relaxed me a little bit. It somehow felt more honest.

I auditioned, this time at least not losing my place halfway through because they let us read our scripts onstage. I didn't learn til later that they'd deliberately handed us terrible sketches that had bombed in years past, to see if we could wring any funny out of them. (I don't think I stood out beyond the material.) Then they asked each of us dumb questions, to see how we'd respond, basically to test our improv skills. I remember my question with perfect accuracy.

"If you could put your sketches in a file, what would that file be called?"

I had no clue what they were talking about.

"The... circular file?" I replied.

A few of them chuckled. I couldn't tell if it was genuine. I found out later that they were making fun of one of their previous members with some inside joke I still don't understand to this day, so they might have been laughing at how clever their diss of that member had been.

I dropped off my serviceable sketch, and left the audition feeling better about myself, because I'd held my own as best I could. I also had no illusions about getting a performing spot, there were several other people I'd watched who were obviously much funnier. My Jack Nicholson dream wasn't working out so well.

A few days later, I got the call - they liked the serviceable sketch I wrote, and wanted me to join the group as a writer. I couldn't have been happier if you told me I'd be a writer on SNL.

And thus began my four-year experience as a member of the University of Arizona's Comedy Corner.

Every Sunday, we'd meet at somebody's house, pass a pad of paper around the room, listing sketch ideas. We'd then have to pitch them to the group, and the group would bat the idea around awhile, to see if they could make anything out of it. We were expected to write the sketches between then and Monday afternoon's rehearsal. Less than twenty-four hours to cook up hilarity. It was a real point of pride with the group that unlike most collegiate comedy groups, we did original written material every week, with little to no improv games, and they enforced with us newbies that writing was incredibly important to the group.

On Monday, the performers would run through all the sketches. If they were funny, they suggested rewrites and joke punch-ups. If they sucked, you got an earful. I got quite a few earfuls those first weeks.

Wednesday was rehearsal number two, and having had two days to rewrite or rethink or come up with something new, the material was expected to be better. Sometimes, that was even the case. The performers would rehearse again, adding more jokes, and starting to figure out which sketches would make the cut. Some weeks, there was a wealth of material. Others, we'd cut half the show, and have to cook up something in the time remaining.

Thursday night, we'd meet at a bar or restaurant, and go over sketches. The performers would try to memorize them while they got drunker and drunker, and the writers would try desperately to add last-minute jokes, or just plead with the performers to not fuck off their material when they performed hung over. Many of the veterans were hyphenates, writer-performers, and their material generally made it to the Friday show, while the rest of us tried our best to fill in the gaps.

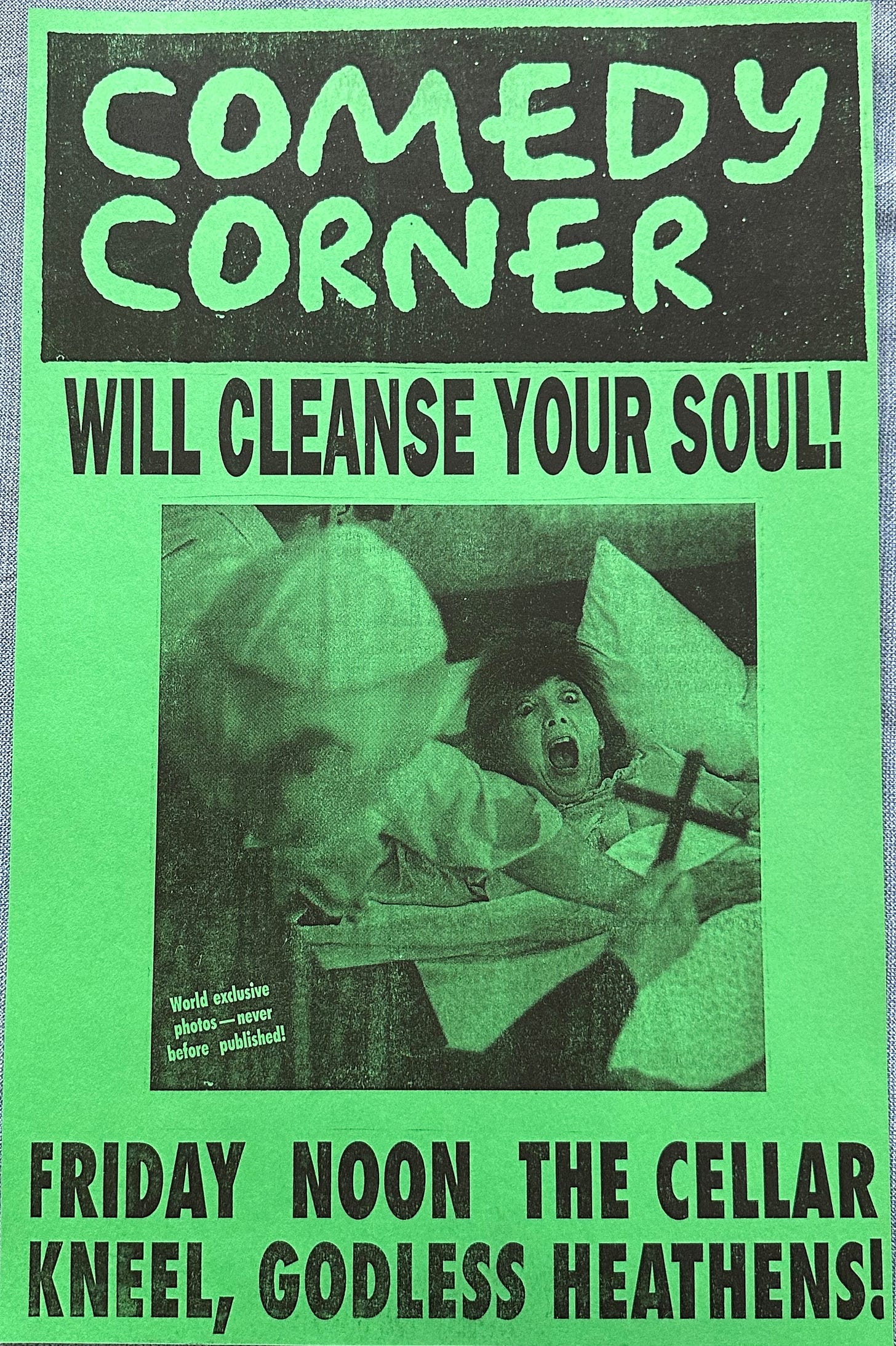

Friday at Noon was the show, free to all. Students would filter in with their lunches, taking up the tables, sitting on the floors, and generally disobeying the fire code. The Cellar could easily hold dozens. When the show was really cooking, there were sometimes hundreds shoehorned in.

And because it was a free show, there was almost zero tolerance from the audience. If a sketch was funny, they cheered and applauded. If a sketch sucked, you could get booed. Nobody threw anything, luckily. But they were not shy about letting you know if they were exuberant or disappointed. Sometimes, a bad sketch would cost you a few good ones, as the audience would still be mad at you, and you'd have to work to get them back.

When the show was over, you had to run to make it to class on time. You got Saturday off, because these are college students we're talking about.

Then, Sunday night, it all started again.

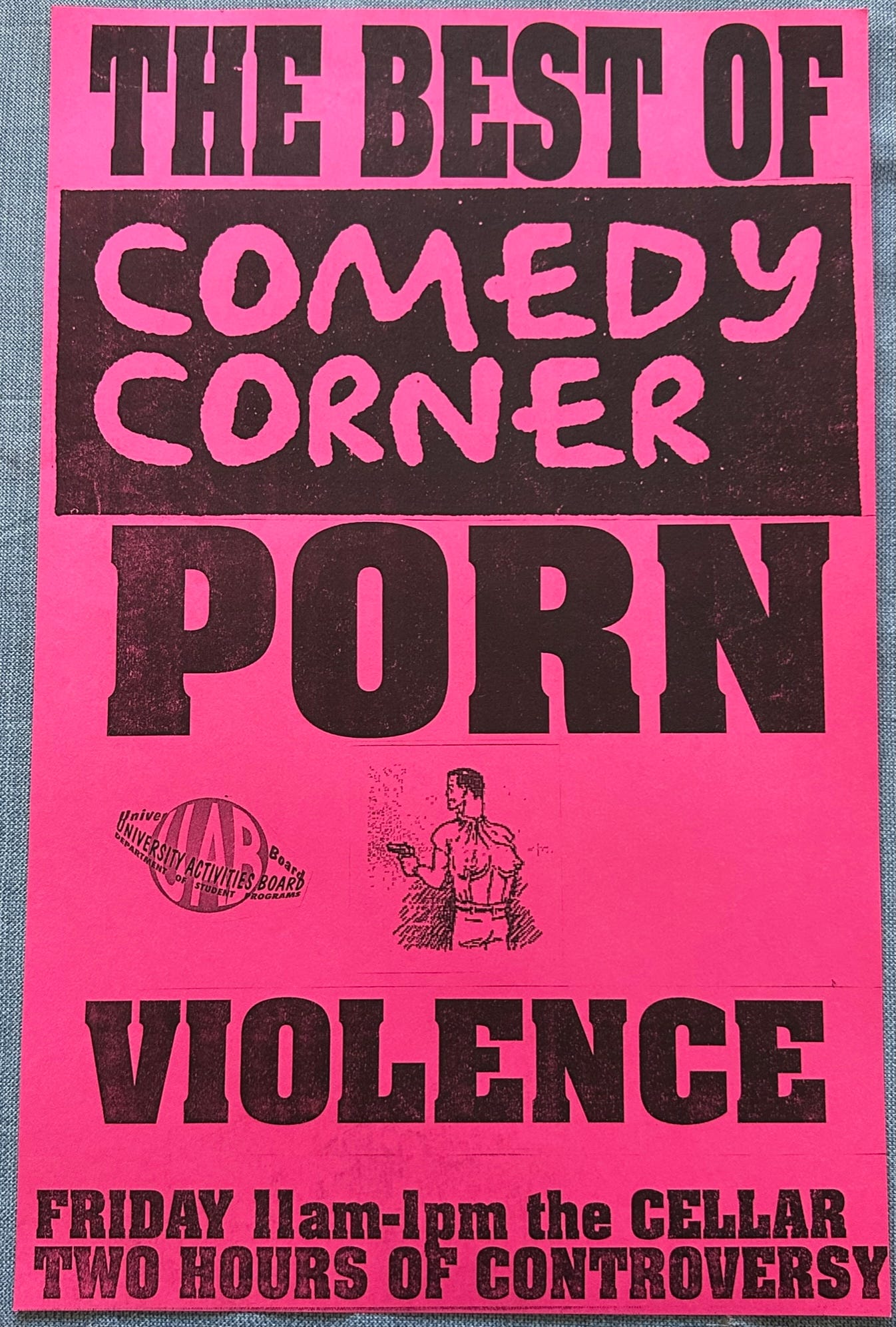

We did roughly thirteen shows a semester that way, including an improv show and a two-hour “Best Of” show to close the semester. The only breaks we got were holidays - if the school was closed on Friday, there was no show. We performed right up to midterms and finals, and you couldn't fuck around and fail your classes, or they'd have to kick you out of the group.

It was the absolute best training for a career in Hollywood I could've asked for.

I learned to write incredibly quickly. In time, a few of the veteran writers started taking me under their wing, helping me work out the kinks. I went from writing a sketch or two a week my freshman year, to sometimes writing more than half the show with my various writing partners my senior year. This translated wonderfully when I moved to L.A. and started writing scripts. I could bang them out with amazing velocity. It took a few years more to learn how to make those fast scripts good, but honestly, part of the lesson of being a writer is finish what you start, and I had already learned that lesson well.

And, of course, everything revolved around the jokes. You had to figure out what was funny. We'd spend hours struggling over how to end sketches the funniest ways possible, and then usually defaulting to stuff we knew would get an easy laugh. In those halcyon days, that often involved someone running in with a prop gun and shooting everyone onstage. It basically was our version of the Monty Python giant foot gag, where a giant foot comes down and squashes everybody. It was weak sauce, but if SNL could get away with the same catchphrases every week, I guess we figured we were allowed our crutch as well.

I eventually moved into performing in the show, and by my senior year, I was in most of the hour, usually half in person, the other half being the disembodied announcer for various sketches. I don't know if I got that job because I had a good voice, or my voice got good because I got stuck with that job, but it was excellent practice for developing a podcasting voice.

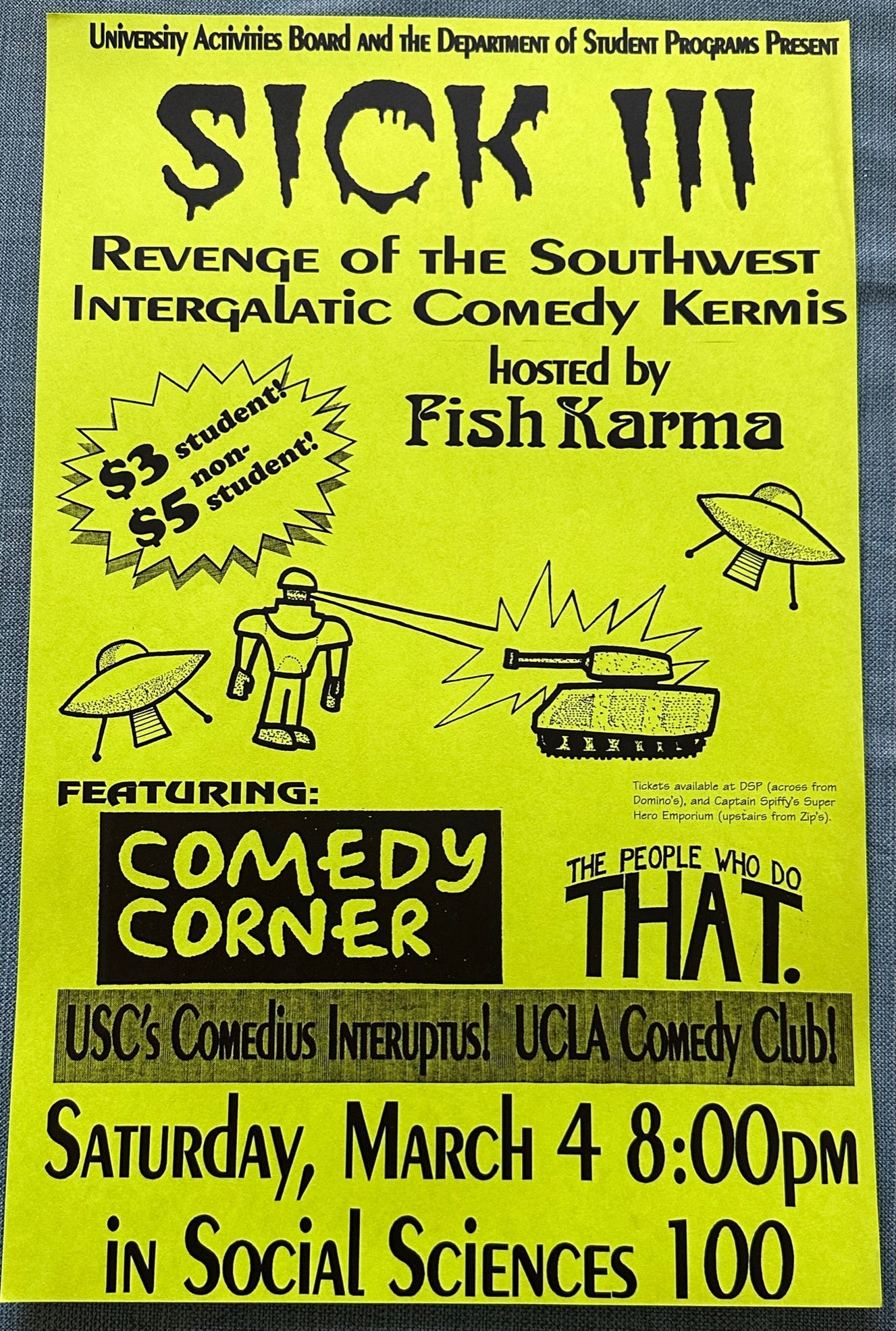

I also became the producer of the show my junior year, which meant I got a desk in the Union Activities Board, where I could make sure the show went off every week without a hitch. I also got to produce an annual comedy festival that my immediate predecessors had gotten off the ground - we called it S.I.C.K., the Southwest Intercollegiate Comedy Kermis (“kermis” being a medieval English word for a festival - I mean, we had to make the "K" work somehow). College comedy groups from across the nation would come and perform together in a giant weekend show. I think my big contribution to that event when I was producing was that I changed the name to the Southwest Intergalactic Comedy Kermis, because I wanted a sci-fi theme for the T-shirts.

For the most part, Comedy Corner was a wonderful space, where you could throw out ideas, try new things, and push yourself. Not that we always did that. Sometimes, when we were low on material, we'd bust out the old tropes, the old jokes, the same old performances. We usually lived to regret it. The audience was good at spotting cynical re-appropriation of material.

Every so often, we'd hit that apex of comedy - we'd stumble upon something new, or truthful. It wasn't every week, but being able to just try anything taught us a wonderful sense of experimentation. We learned the rules, but we also learned to break them. By the time we graduated, most of us had more writing and performance hours under our belt than almost any other discipline on campus.

Downside? Of course. Because Comedy Corner in those days reflected Hollywood and SNL in more ways than just teaching you an incredible work ethic - we also had embraced the 90s ethos of cruel comedy. Somebody's overweight? Let the fat jokes commence. Women? Sex jokes and filth abound. One of the new guys was given the moniker "Dogpile," because during auditions, all of the vets had spontaneously dogpiled him, probably because he was shorter and skinnier than most people there. He had to put up with being dogpiled several times a week for the first year. It was funny, y'know, the first few times. Then he rightfully got sick of it. Which only made it happen more often. They turned it into a semi-weekly sketch, so he could look forward to getting cranked within an inch of his life on a regular basis.

Ostensibly, this was all intended to give us a thicker skin and make our comedy better, which, in some ways, it did. But today, that environment would be classified as toxic. And those of us in the mix, I guess we figured there was no better alternative. Suffering breeds comedy, right? We prided ourselves on being able to make any kind of joke, no matter whose sensibilities might be offended. In fact, if someone was offended, that tended to act as proof to us that we were doing our job.

Maybe some of that is even true. There's a few times when people took offense to a sketch I wrote or a poster I made advertising the show, that was probably over-reactionary. Sometimes I did it deliberately to provoke a reaction. And maybe sometimes, that was the right thing to do. Because sometimes, you need a kick in the teeth to wake you up. And some of the best comedy is the kind that wakes you up.

But there are plenty of other times where we were fooling ourselves. Where we were hurtful rather than observant. I don't regret trying to push boundaries to try and actually say something, but sometimes, we weren't saying anything except that we were young and ignorant. I like to think that I wasn't being cruel just to be cruel, but there comes a point where intention doesn't get you off the hook.

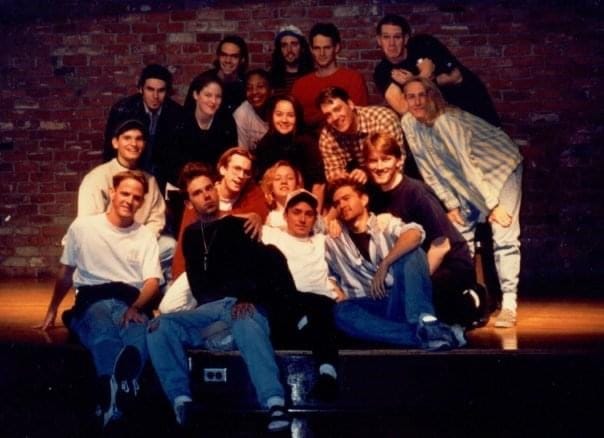

And of course, we had the common 90s problem of too many white dudes in the group. We'd make an attempt to include diverse voices, which sometimes got us a makeup of up to ten, maybe twenty percent non-white dudes! So, yeah, not exactly setting the world on fire with our inclusiveness.

The year after I graduated, my younger brother came to U of A as a freshman, and ended up joining the group, ensuring an eight-year Nelson dynasty in Comedy Corner. He went on to become the producer of the show at a younger age than I did. When I would occasionally visit and join the show as a guest, I was impressed that the group had improved the environment since I'd been gone. They were genuinely friendlier with each other, and I think it reflected in their work. They had exploded our work ethic, now including not only the weekly sketch show and the annual festival, but a weekly improv show, and a daily morning radio show. They had their own moments of casual cruelty, but they were gentler with each others' feelings. It was good to see.

Comedy Corner is still around to this day, making it well over a fifty-year institution. The U of A has changed and undergone renovations, the Cellar was bulldozed, and the coveted Friday noon spot was lost. Now they perform mid-week, in the evening, in another building, on another stage. Last I heard, they had shifted fully from original sketches to improv, the radio show and sketch show long gone. So basically, a completely different type of group, doing a wholly different show. I have to admit it saddens me a little - we always prided ourselves in being one of the few sketch comedy groups in an ocean of improv groups, but the circle turns, and maybe one day it'll turn back to sketch writing.

And if it doesn't, hopefully they're still learning the skills that we did - how to think on your feet, how to get an audience where you want them, how to digest criticism and make your work better. The people I worked and played with have gone on to be actors, writers, directors, comedians, podcasters, video game designers, musicians, greeting card writers, lawyers, teachers, the whole spectrum, and I'd bet green money that most, if not all of them, would credit their time in Comedy Corner to improving their skills in whatever field they chose.

(I didn't learn until I'd been in Hollywood a few years that Jack Nicholson had mostly been a failed actor, up to the point he started screenwriting movies. So I'm basically halfway to becoming a famous actor! Now I just need to figure out that whole Stephen King thing.)

By the way, this was not the last sketch comedy group I was in. There were two more on the horizon, and perhaps one day, children, if you’re good, I’ll tell you all about them.

© 2023